|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Having used some of Python's built-in types, we are ready to create a user-defined type: the Point.

Consider the concept of a mathematical point. In two dimensions, a point is two numbers (coordinates) that are treated collectively as a single object. In mathematical notation, points are often written in parentheses with a comma separating the coordinates. For example, (0, 0) represents the origin, and (x, y) represents the point x units to the right and y units up from the origin.

A natural way to represent a point in Python is with two floating-point values. The question, then, is how to group these two values into a compound object. The quick and dirty solution is to use a list or tuple, and for some applications that might be the best choice.

An alternative is to define a new user-defined compound type, also called a class. This approach involves a bit more effort, but it has advantages that will be apparent soon.

A class definition looks like this:

class Point:

pass

Class definitions can appear anywhere in a program, but they are usually near the beginning (after the import statements). The syntax rules for a class definition are the same as for other compound statements (see Section 4.4).

This definition creates a new class called Point. The pass statement has no effect; it is only necessary because a compound statement must have something in its body.

By creating the Point class, we created a new type, also called Point. The members of this type are called instances of the type or objects. Creating a new instance is called instantiation. To instantiate a Point object, we call a function named (you guessed it) Point:

blank = Point()

The variable blank is assigned a reference to a new

Point object. A function like Point that creates

new objects is called a constructor.

Click here for feedback

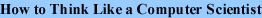

We can add new data to an instance using dot notation:

>>> blank.x = 3.0

>>> blank.y = 4.0

This syntax is similar to the syntax for selecting a variable from a module, such as math.pi or string.uppercase. In this case, though, we are selecting a data item from an instance. These named items are called attributes.

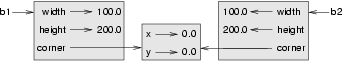

The following state diagram shows the result of these assignments:

The variable blank refers to a Point object, which contains two attributes. Each attribute refers to a floating-point number.

We can read the value of an attribute using the same syntax:

>>> print blank.y

4.0

>>> x = blank.x

>>> print x

3.0

The expression blank.x means, "Go to the object blankrefers to and get the value of x." In this case, we assign that value to a variable named x. There is no conflict between the variable x and the attribute x. The purpose of dot notation is to identify which variable you are referring to unambiguously.

You can use dot notation as part of any expression, so the following statements are legal:

print '(' + str(blank.x) + ', ' + str(blank.y) + ')'

distanceSquared = blank.x * blank.x + blank.y * blank.y

The first line outputs (3.0, 4.0); the second line calculates the value 25.0.

You might be tempted to print the value of blank itself:

>>> print blank

<__main__.Point instance at 80f8e70>

The result indicates that blank is an instance of the Point class and it was defined in __main__. 80f8e70is the unique identifier for this object, written in hexadecimal (base 16). This is probably not the most informative way to display a Point object. You will see how to change it shortly.

As an exercise, create and print a Point object, and then use id to print the object's unique identifier. Translate the hexadecimal form into decimal and confirm that they match.Click here for feedback

You can pass an instance as a parameter in the usual way. For example:

def printPoint(p):

print '(' + str(p.x) + ', ' + str(p.y) + ')'

printPoint takes a point as an argument and displays it in the standard format. If you call printPoint(blank), the output is (3.0, 4.0).

As an exercise, rewrite the distance function from Section 5.2 so that it takes two Points as parameters instead of four numbers.Click here for feedback

The meaning of the word "same" seems perfectly clear until you give it some thought, and then you realize there is more to it than you expected.

For example, if you say, "Chris and I have the same car," you mean that his car and yours are the same make and model, but that they are two different cars. If you say, "Chris and I have the same mother," you mean that his mother and yours are the same person. * Note So the idea of "sameness" is different depending on the context.

When you talk about objects, there is a similar ambiguity. For example, if two Points are the same, does that mean they contain the same data (coordinates) or that they are actually the same object?

To find out if two references refer to the same object, use the == operator. For example:

>>> p1 = Point()

>>> p1.x = 3

>>> p1.y = 4

>>> p2 = Point()

>>> p2.x = 3

>>> p2.y = 4

>>> p1 == p2

0

Even though p1 and p2 contain the same coordinates, they are not the same object. If we assign p1 to p2, then the two variables are aliases of the same object:

>>> p2 = p1

>>> p1 == p2

1

This type of equality is called shallow equality because it compares only the references, not the contents of the objects.

To compare the contents of the objects deep equality we

can write a function called samePoint:

def samePoint(p1, p2) :

return (p1.x == p2.x) and (p1.y == p2.y)

Now if we create two different objects that contain the same data, we can use samePoint to find out if they represent the same point.

>>> p1 = Point()

>>> p1.x = 3

>>> p1.y = 4

>>> p2 = Point()

>>> p2.x = 3

>>> p2.y = 4

>>> samePoint(p1, p2)

1

Of course, if the two variables refer to the same object,

they have both shallow and deep equality.

Click here for feedback

Let's say that we want a class to represent a rectangle. The question is, what information do we have to provide in order to specify a rectangle? To keep things simple, assume that the rectangle is oriented either vertically or horizontally, never at an angle.

There are a few possibilities: we could specify the center of the rectangle (two coordinates) and its size (width and height); or we could specify one of the corners and the size; or we could specify two opposing corners. A conventional choice is to specify the upper-left corner of the rectangle and the size.

Again, we'll define a new class:

class Rectangle:

pass

And instantiate it:

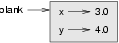

box = Rectangle()

box.width = 100.0

box.height = 200.0

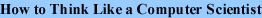

This code creates a new Rectangle object with two floating-point attributes. To specify the upper-left corner, we can embed an object within an object!

box.corner = Point()

box.corner.x = 0.0;

box.corner.y = 0.0;

The dot operator composes. The expression box.corner.x means, "Go to the object box refers to and select the attribute named corner; then go to that object and select the attribute named x."

The figure shows the state of this object:

Functions can return instances. For example, findCentertakes a Rectangle as an argument and returns a Pointthat contains the coordinates of the center of the Rectangle:

def findCenter(box):

p = Point()

p.x = box.corner.x + box.width/2.0

p.y = box.corner.y + box.height/2.0

return p

To call this function, pass box as an argument and assign the result to a variable:

>>> center = findCenter(box)

>>> printPoint(center)

(50.0, 100.0)

We can change the state of an object by making an assignment to one of its attributes. For example, to change the size of a rectangle without changing its position, we could modify the values of width and height:

box.width = box.width + 50

box.height = box.height + 100

We could encapsulate this code in a method and generalize it to grow the rectangle by any amount:

def growRect(box, dwidth, dheight) :

box.width = box.width + dwidth

box.height = box.height + dheight

The variables dwidth and dheight indicate how much the rectangle should grow in each direction. Invoking this method has the effect of modifying the Rectangle that is passed as an argument.

For example, we could create a new Rectangle named boband pass it to growRect:

>>> bob = Rectangle()

>>> bob.width = 100.0

>>> bob.height = 200.0

>>> bob.corner = Point()

>>> bob.corner.x = 0.0;

>>> bob.corner.y = 0.0;

>>> growRect(bob, 50, 100)

While growRect is running, the parameter box is an alias for bob. Any changes made to box also affect bob.

As an exercise, write a function named moveRect that takes a Rectangle and two parameters named dx and dy. It should change the location of the rectangle by adding dxto the x coordinate of corner and adding dyto the y coordinate of corner.Click here for feedback

Aliasing can make a program difficult to read because changes made in one place might have unexpected effects in another place. It is hard to keep track of all the variables that might refer to a given object.

Copying an object is often an alternative to aliasing. The copy module contains a function called copy that can duplicate any object:

>>> import copy

>>> p1 = Point()

>>> p1.x = 3

>>> p1.y = 4

>>> p2 = copy.copy(p1)

>>> p1 == p2

0

>>> samePoint(p1, p2)

1

Once we import the copy module, we can use the copy method to make a new Point. p1 and p2 are not the same point, but they contain the same data.

To copy a simple object like a Point, which doesn't contain any embedded objects, copy is sufficient. This is called shallow copying.

For something like a Rectangle, which contains a reference to a Point, copy doesn't do quite the right thing. It copies the reference to the Point object, so both the old Rectangle and the new one refer to a single Point.

If we create a box, b1, in the usual way and then make a copy, b2, using copy, the resulting state diagram looks like this:

This is almost certainly not what we want. In this case, invoking growRect on one of the Rectangles would not affect the other, but invoking moveRect on either would affect both! This behavior is confusing and error-prone.

Fortunately, the copy module contains a method named deepcopy that copies not only the object but also any embedded objects. You will not be surprised to learn that this operation is called a deep copy.

>>> b2 = copy.deepcopy(b1)

Now b1 and b2 are completely separate objects.

We can use deepcopy to rewrite growRect so that instead of modifying an existing Rectangle, it creates a new Rectangle that has the same location as the old one but new dimensions:

def growRect(box, dwidth, dheight) :

import copy

newBox = copy.deepcopy(box)

newBox.width = newBox.width + dwidth

newBox.height = newBox.height + dheight

return newBox

An an exercise, rewrite moveRect so that it creates and returns a new Rectangle instead of modifying the old one.Click here for feedback

|

|

|

|

|

|

|