We have used many of Python’s built-in types; now we are going to define a new type. As an example, we will create a type called Point that represents a point in two-dimensional space.

In mathematical notation, points are often written in parentheses with a comma separating the coordinates. For example, (0, 0) represents the origin, and (x, y) represents the point x units to the right and y units up from the origin.

There are several ways we might represent points in Python:

Creating a new type is (a little) more complicated than the other options, but it has advantages that will be apparent soon.

A user-defined type is also called a class. A class definition looks like this:

class Point(object):

"""represents a point in 2-D space"""

This header indicates that the new class is a Point, which is a kind of object, which is a built-in type.

The body is a docstring that explains what the class is for. You can define variables and functions inside a class definition, but we will get back to that later.

Defining a class named Point creates a class object.

>>> print Point <class '__main__.Point'>

Because Point is defined at the top level, its “full

name” is __main__.Point.

The class object is like a factory for creating objects. To create a Point, you call Point as if it were a function.

>>> blank = Point() >>> print blank <__main__.Point instance at 0xb7e9d3ac>

The return value is a reference to a Point object, which we assign to blank. Creating a new object is called instantiation, and the object is an instance of the class.

When you print an instance, Python tells you what class it belongs to and where it is stored in memory (the prefix 0x means that the following number is in hexadecimal).

You can assign values to an instance using dot notation:

>>> blank.x = 3.0 >>> blank.y = 4.0

This syntax is similar to the syntax for selecting a variable from a module, such as math.pi or string.whitespace. In this case, though, we are assigning values to named elements of an object. These elements are called attributes.

As a noun, “AT-trib-ute” is pronounced with emphasis on the first syllable, as opposed to “a-TRIB-ute,” which is a verb.

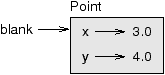

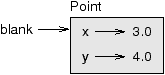

The following diagram shows the result of these assignments. A state diagram that shows an object and its attributes is called an object diagram:

The variable blank refers to a Point object, which contains two attributes. Each attribute refers to a floating-point number.

You can read the value of an attribute using the same syntax:

>>> print blank.y 4.0 >>> x = blank.x >>> print x 3.0

The expression blank.x means, “Go to the object blank refers to and get the value of x.” In this case, we assign that value to a variable named x. There is no conflict between the variable x and the attribute x.

You can use dot notation as part of any expression. For example:

>>> print '(%g, %g)' % (blank.x, blank.y) (3.0, 4.0) >>> distance = math.sqrt(blank.x**2 + blank.y**2) >>> print distance 5.0

You can pass an instance as an argument in the usual way. For example:

def print_point(p):

print '(%g, %g)' % (p.x, p.y)

print_point takes a point as an argument and displays it in

mathematical notation. To invoke it, you can pass blank as

an argument:

>>> print_point(blank) (3.0, 4.0)

Inside the function, p is an alias for blank, so if the function modifies p, blank changes.

Sometimes it is obvious what the attributes of an object should be, but other times you have to make decisions. For example, imagine you are designing a class to represent rectangles. What attributes would you use to specify the location and size of a rectangle? You can ignore angle; to keep things simple, assume that the rectangle is either vertical or horizontal.

There are at least two possibilities:

At this point it is hard to say whether either is better than the other, so we’ll implement the first one, just as an example.

Here is the class definition:

class Rectangle(object):

"""represent a rectangle.

attributes: width, height, corner.

"""

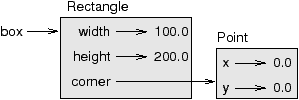

The docstring lists the attributes: width and height are numbers; corner is a Point object that specifies the lower-left corner.

To represent a rectangle, you have to instantiate a Rectangle object and assign values to the attributes:

box = Rectangle() box.width = 100.0 box.height = 200.0 box.corner = Point() box.corner.x = 0.0 box.corner.y = 0.0

The expression box.corner.x means, “Go to the object box refers to and select the attribute named corner; then go to that object and select the attribute named x.”

The figure shows the state of this object:

An object that is an attribute of another object is embedded.

Functions can return instances. For example, find_center

takes a Rectangle as an argument and returns a Point

that contains the coordinates of the center of the Rectangle:

def find_center(box):

p = Point()

p.x = box.corner.x + box.width/2.0

p.y = box.corner.y + box.height/2.0

return p

Here is an example that passes box as an argument and assigns the resulting Point to center:

>>> center = find_center(box) >>> print_point(center) (50.0, 100.0)

You can change the state of an object by making an assignment to one of its attributes. For example, to change the size of a rectangle without changing its position, you can modify the values of width and height:

box.width = box.width + 50 box.height = box.width + 100

You can also write functions that modify objects. For example,

grow_rectangle takes a Rectangle object and two numbers,

dwidth and dheight, and adds the numbers to the

width and height of the rectangle:

def grow_rectangle(rect, dwidth, dheight) :

rect.width += dwidth

rect.height += dheight

Here is an example that demonstrates the effect:

>>> print box.width 100.0 >>> print box.height 200.0 >>> grow_rectangle(box, 50, 100) >>> print box.width 150.0 >>> print box.height 300.0

Inside the function, rect is an alias for box, so if the function modifies rect, box changes.

move_rectangle that takes

a Rectangle and two numbers named dx and dy. It

should change the location of the rectangle by adding dx

to the x coordinate of corner and adding dy

to the y coordinate of corner.

Aliasing can make a program difficult to read because changes in one place might have unexpected effects in another place. It is hard to keep track of all the variables that might refer to a given object.

Copying an object is often an alternative to aliasing. The copy module contains a function called copy that can duplicate any object:

>>> p1 = Point() >>> p1.x = 3.0 >>> p1.y = 4.0 >>> import copy >>> p2 = copy.copy(p1)

p1 and p2 contain the same data, but they are not the same Point.

>>> print_point(p1) (3.0, 4.0) >>> print_point(p2) (3.0, 4.0) >>> p1 is p2 False >>> p1 == p2 False

The is operator indicates that p1 and p2 are not the same object, which is what we expected. But you might have expected == to yield True because these points contain the same data. In that case, you will be disappointed to learn that for instances, the default behavior of the == operator is the same as the is operator; it checks object identity, not object equivalence. This behavior can be changed—we’ll see how later.

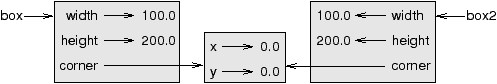

If you use copy.copy to duplicate a Rectangle, you will find that it copies the Rectangle object but not the embedded Point.

>>> box2 = copy.copy(box) >>> box2 is box False >>> box2.corner is box.corner True

Here is what the object diagram looks like:

This operation is called a shallow copy because it copies the object and any references it contains, but not the embedded objects.

For most applications, this is not what you want. In this example,

invoking grow_rectangle on one of the Rectangles would not

affect the other, but invoking move_rectangle on either would

affect both! This behavior is confusing and error-prone.

Fortunately, the copy module contains a method named deepcopy that copies not only the object but also the objects it refers to, and the objects they refer to, and so on. You will not be surprised to learn that this operation is called a deep copy.

>>> box3 = copy.deepcopy(box) >>> box3 is box False >>> box3.corner is box.corner False

box3 and box are completely separate objects.

move_rectangle that creates and

returns a new Rectangle instead of modifying the old one.

When you start working with objects, you are likely to encounter some new exceptions. If you try to access an attribute that doesn’t exist, you get an AttributeError:

>>> p = Point() >>> print p.z AttributeError: Point instance has no attribute 'z'

If you are not sure what type an object is, you can ask:

>>> type(p) <type '__main__.Point'>

If you are not sure whether an object has a particular attribute, you can use the built-in function hasattr:

>>> hasattr(p, 'x') True >>> hasattr(p, 'z') False

The first argument can be any object; the second argument is a string that contains the name of the attribute.

World.py, which is part of Swampy (see Chapter 4), contains a class definition for a user-defined type called World. You can import it like this:

from World import World

This version of the import statement imports the World class from the World module. The following code creates a World object and calls the mainloop method, which waits for the user.

world = World() world.mainloop()

A window should appear with a title bar and an empty square.

We will use this window to draw Points,

Rectangles and other shapes.

Add the following lines before calling

calling and run the program again

canvas = world.ca(width=500, height=500, background='white') bbox = [[-150,-100], [150, 100]] canvas.rectangle(bbox, outline='black', width=2, fill='green4')

You should see a green rectangle with a black outline. The first line creates a Canvas, which appears in the window as a white square. The Canvas object provides methods like rectangle for drawing various shapes.

bbox is a list of lists that represents the “bounding box” of the rectangle. The first pair of coordinates is the lower-left corner of the rectangle; the second pair is the upper-right corner.

You can draw a circle like this:

canvas.circle([-25,0], 70, outline=None, fill='red')

The first parameter is the coordinate pair for the center of the circle; the second parameter is the radius.

If you add this line to the program, the result should resemble the national flag of Bangladesh (see wikipedia.org/wiki/Gallery_of_sovereign-state_flags).

draw_rectangle that takes a

Canvas and a Rectangle as arguments and draws a

representation of the Rectangle on the Canvas.draw_rectangle so that it uses the color attribute as

the fill color.draw_point that takes a

Canvas and a Point as arguments and draws a

representation of the Point on the Canvas.draw_circle that draws circles on the canvas.points = [[-150,-100], [150, 100], [150, -100]] canvas.polygon(points, fill='blue')

I have written a small program that lists the available colors; you can download it from thinkpython.com/code/color_list.py.